Listening Together, The Salinas Soil Project

Foreward and Gratitude by Callie Chappell

Andrea Leon loading portable Nanopore DNA Sequencer on a picnic blanket in Natividad Creek Park. Community collaborator Adrian looks on while recording.

In November and December 2025, Andrea Leon Tenorio (a Stanford undergraduate student studying Bioengineering) and I co-facilitated a community-based soil sequencing project in a community garden and public park in Salinas, California. This was meant as a pilot program to support community sovereignty in biology research and biotechnology. We wanted to explore biology with community, in community, to demonstrate that science can happen anywhere—including picnic tables in the park, backyards, and kitchen tables. Community leaders included Leticia Hernandez (Local Urban Gardeners, Natividad Creek Park), Adrian Salazar Huazo (Alisal High School), David Rosales-Nieto (Alisal High School), Joe Perez (CSU Monterey Bay), Tatiana Chavez Pacheco (CSU Monterey Bay), Kenia Cortes-Campos (CSU Monterey Bay), Adrian Tamayo (La Paz Middle School), and Robin Lee. Special thanks to Leonel Navarro and Patti Fashing for opening their backyards and homes to us during a rainy workshop day. Rolando Cruz Perez was a major supporter and his work and vision served as a significant inspiration for the project, along with Corinne Okada Takara, Melissa Ortiz, Ana Ibarra, and many others.

Now that the program has concluded, we wanted to share our reflections in this blog post. Andrea wrote the blog post and I took the photos. We hope you enjoy!

Group Photos from the four Saturday Workshops

Reflection by Andrea Leon

INtroduction

This workshop series grew from a shared desire to explore the local garden and creek in Salinas alongside the community, guided by the questions people themselves were curious about.

Portable Nanopore DNA Sequencer that can be plugged into a laptop’s USB port

After being given a small, portable DNA reader at an IndigiData conference, I shared the idea with the BioJam organizing team: to use this tool so community members in Salinas could ask scientific questions relevant to their own lives and environment. BioJam, a science and art program for migrant youth to reimagine their role in biotechnology, was deeply invested in expanding this vision into year-round community workshops. We were excited to learn how to use this new tool together—and also nervous, because none of us had done this before.

La Paz Middle School student preparing DNA for sequencing at picnic table in Natividad Creek Park

Over four days, we explored soil biodiversity together: collecting soil, making more copies of DNA so we could see it, preparing it so it could be read, reading it, and finally looking at the data and imagining what could come next. Along the way, participants reflected on how this experience changed how they see science, scientists, and their own place within it.

More than 35 people participated across the workshops, including children, youth, elders, teachers, scientists, artists, gardeners, and community members. The group was multigenerational and multidisciplinary, bringing together many ways of knowing. Some participants had long histories in science, while others were engaging with scientific tools for the first time. Learning happened through conversation, shared work, and care for one another.

With our shared purpose and questions in mind, we began not with tools or data, but with the land itself. Before looking beneath—to the soil—we spent time noticing what was already visible on the surface.

Plants: What We Can See

Soil sampling in Natividad Creek Park’s community garden

Plants are often the first way we notice the earth speaks to us.

In Salinas, we gathered at the community garden in Natividad Creek Park, where a creek runs through the land. As the water moves, the plants change with it. Walking alongside the creek, we noticed how vegetation shifts from place to place. Where the land is nourished, plants grow strong and diverse. Where the land is stressed, the plants show it.

In our workshops, we began here. We walked together through the garden and the park, slowing down to look closely at plants, to appreciate our surroundings, and to be curious about the living world around us.

Plants teach us how to pay attention.

Roots: What allows us to grow and holds us steady

Leticia Hernandez preparing DNA for sequencing

This project was rooted in people from many different backgrounds and areas of expertise. Across four Saturdays, youth, community members, students, and researchers returned to the same place to learn together. Some joined for one day, others for all four. The work continued because it was shared.

Leticia Hernandez brought deep knowledge as a local urban gardener and community leader. Her long relationship with the land helped ground the project in care, close observation, and responsibility to place. Leticia led an experiment to study how the park affected the diversity of soil biodiversity, as water flowed off agricultural fields through the park via Natividad Creek Park.

Adrian Salazar Huazo, an 11th grader from Alisal High School and a former BioJam participant, joined as both a learner and a leader. His curiosity and commitment shaped the workshop atmosphere and design, and he led an experiment to test whether la Milpa, a traditional permaculture technique often referrred to as the Three Sisters, increased soil microbiome diversity in the garden, compared to strawberry monoculture or growing no plants at all.

Adrian Salazar Huazo preparing to load a DNA gel

I, Annel Andrea Leon Tenorio, am a bioengineering undergraduate at Stanford University and a BioJam leader. I came to this work carrying my roots—from the Andes of Peru—and a desire to practice science as listening, relationship, and return to community, bringing together bioengineering, technology, and care for land and people.

Dr. Callie Chappell is a biology researcher at Stanford and BioJam leader who supported and guided the project as an artist-activist-scientist. They worked alongside the community to make tools, learning, and leadership accessible, rather than directing from above.

Students from California State University, Monterey Bay joined through service learning, connecting classroom science to real-world, community-based work and building confidence through participation.

As relationships formed, participants reflected on belonging. One shared, “I feel like in the end I saw it more as belonging to the community and I was glad I could be a part of that.”

Together, these roots held us steady—so we could look deeper.

Soil: The living beneath that brings nutrients to all above

We shared our findings by painting rocks that represented the types of bacteria found in the soil at the creek and garden. These painted rocks are in the community garden and informational sign in the Little Free Library.

On the first day of the workshop series, we gathered in community—meeting one another and shaping the atmosphere for the rest of the workshops. In the afternoon, we collected soil together from the community garden, the creek, and paths throughout the park. We talked about where each sample came from and why that place mattered. The soil sampling sites were selected by Leticia and Adrian.

On the second day, we made more copies of the DNA extracted from the soil so we could see it clearly on a DNA visualizing gel. This day was rainy, so two community members generously opened their homes for our community experiments.

On the third day, we prepared the DNA and used a small, portable reader to begin exploring what lives in the soil. For many participants, this was the first time seeing DNA sequencing happen up close.

On the final day, we looked at the results together. We talked about what we noticed, what surprised us, and what questions remained. We focused on what the soil was telling us and how we might continue listening. One participant reflected, “I see science as belonging to us as a collective. I feel like I can call myself a soil scientist with confidence.”

When asked how this experience changed their views of science and scientists, one participant said: “Have been in the sciences for decades.”

Through this process, the life within the soil became apparent—and in turn, nurtured our growth.

What did we learn? (An aside by Callie)

Our community members addressed two scientific projects, one looking at the differences in the soil microbiome between garden plots with la Milpa and without, and the other looking at how biodiversity differs throughout the park.

Milpa project

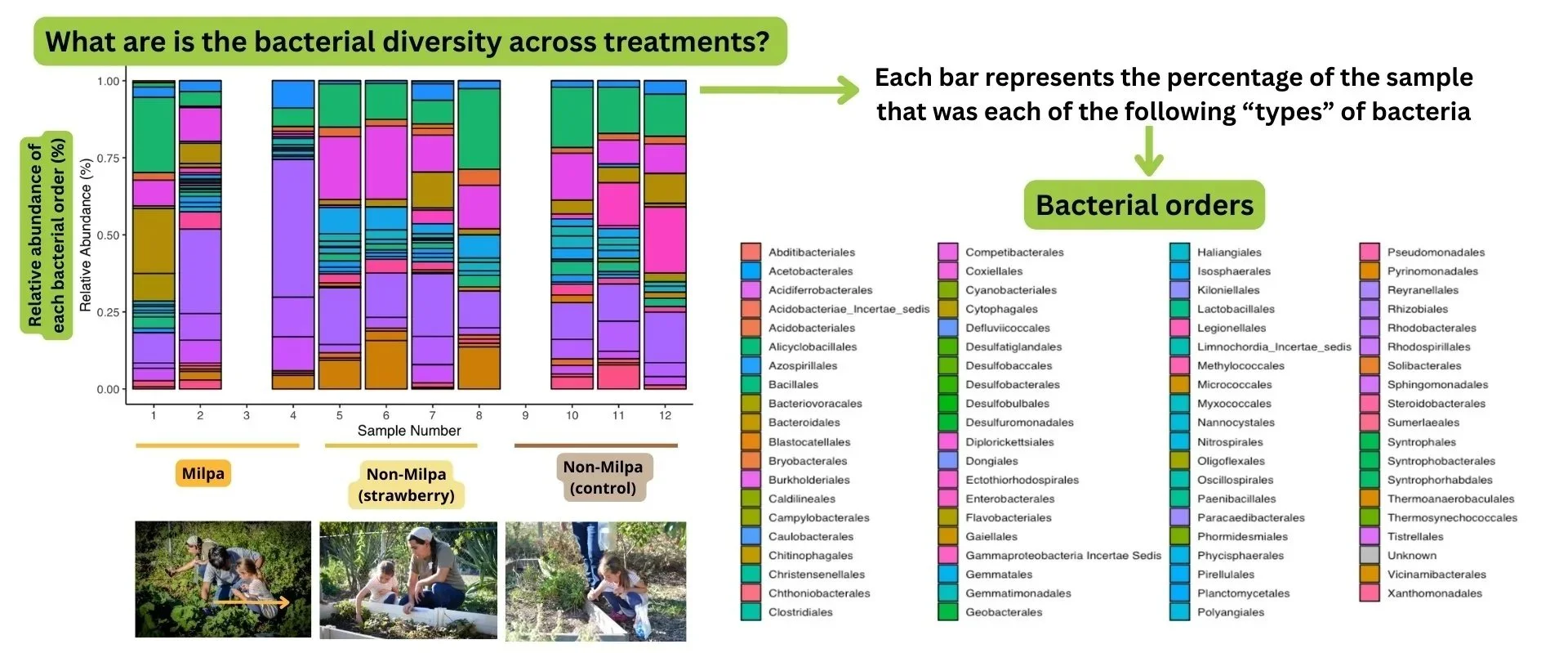

Figure 1: Comparison of types of microbes found in Milpa and non-Milpa garden plots.

Adrian wondered whether Milpas can increase the biodiversity of bacteria in soil. To test this, community members sampled garden plots where Milpa had previously been planted, a garden plot with strawberry monoculture, and a garden plot with no plants.

We used the DNA sequencing results to see what types of bacteria were found in Milpa and non-Milpa plots (shown in Figure 1).

Park Biodiversity along Natividad Creek

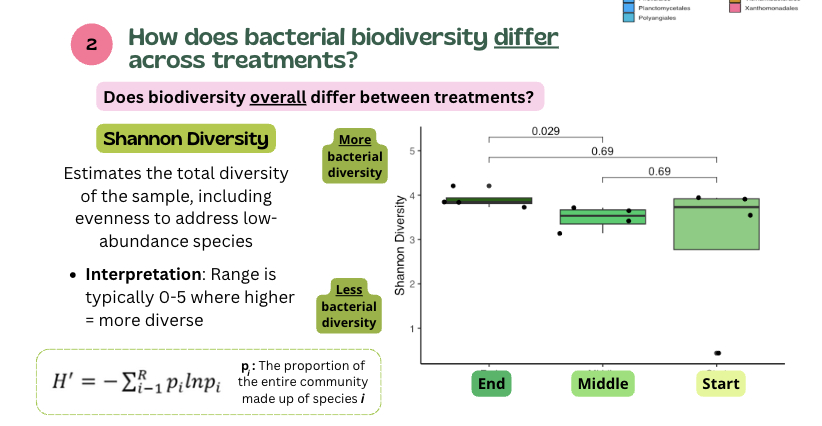

Leticia wondered whether Natividad Creek picks up or loses microbial diversity as it passes through the community park? Her team sampled at three points of the park: the beginning where water was flowing directly off agricultural fields, in the middle, and the end of the park.

Leticia hypothesized that “microbial diversity will increase as the creek passes through the park, where slower flow and more vegetation may create better conditions for microbes to thrive.”

We found that biodiversity does increase between the middle and end of the park, but not the middle (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Biodiversity does increase from middle to end of the park, but not at the start of the park.

Next Steps, Taller Tierra Viva

Group of scientists harvesting soil for DNA sequencing

This work continues through Taller Tierra Viva, a community workshop open to all on January 17th-18th. Community members of all ages are invited to explore soil biodiversity in Salinas by bringing soil from places that matter to them—gardens, neighborhoods, and shared spaces—and learning together through observation and DNA. We are excited to use the new community space at the new community lab in the Steinbeck Center (1 Main Street, Salinas), managed by the Hartnell Foundation’s K-12 STEAM Program.

If you are interested in joining, email Callie Chappell (calliech@stanford.edu) before January 2nd, 2026.